Low back pain (LBP) is a common cause of disability in US adults, with more than 80 percent of the population experiencing LBP in their lifetime.1 When LBP persists for longer than three months, it’s considered a chronic condition and can severely impact quality of life.2 Discogenic pain is the result of deterioration of the connective tissue discs between the spine vertebrae — it is a leading cause of chronic LBP.3 As the disc deteriorates, it may lose flexibility, allowing outer layers to crack or peel away. The patient’s inflammatory response senses this change and reacts, penetrating the disc with an overgrowth of nerves that carry pain signals.4

Limitations of Conventional Management Options

- These options offer short-term pain relief, but are not suited for long-term care, as they have a limited duration of action and associated risks.5

- Comes with complication risks, long recovery times and the potential for stress on vertebrae near the fused segment.6

Advantages of Using COOLIEF* Cooled Radiofrequency

Advantages of Using COOLIEF* Cooled Radiofrequency

COOLIEF* Cooled RF can bridge the gap between short-term pain relief treatments and surgery by providing a minimally invasive, non-opioid procedure for discogenic back pain.

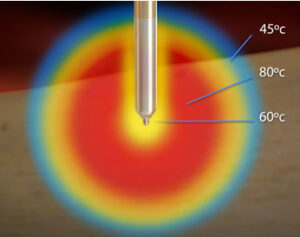

Specifically designed to treat complex anatomy of variable nerve courses, COOLIEF* Cooled RF uses water-cooled technology that enables more RF energy to safely deactivate pain-transmitting sensory nerves. This creates a larger, spherical lesion that distally projects 45% or greater beyond the probe’s tip, allowing physicians to approach the target nerve from any angle.

- Demonstrates up to 24 months pain relief with improved physical function and a reduction in opioid medication usage

- Delivers up to 3.7x more energy than standard RF

Comparing IDB to CMM

A 2016 study published in Spine, and follow-up study published in Pain Medicine in 2017, compared the effectiveness of IDB and CMM in the treatment of discogenic LBP. CMM consisted of self-care, analgesic anti-inflammatory medication, nonsurgical interventions, physical therapy and cognitive therapy. Subjects were evaluated for pain, disability, function and safety at one, three and six months using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), ODI, Patients Global Impression of Change (PGIC) and SF-36.

6-MONTH RESULTS

Average VAS Pain Scores for 6-Month Time Point

Pain

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported an average decrease of 2.4 points from baseline VAS

Subjects who received CMM alone reported a 0.56-point decrease from baseline.

Function

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported an average increase of 18 points from SF-36 baseline.

Comparably, subjects who received CMM alone reported a 17-point increase from baseline.

Disability

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported an average decrease of 11 points from baseline ODI.

Subjects who received CMM alone reported a 0.22-point increase from baseline.

Patient Satisfaction

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported an average decrease of 1.7 points from baseline PGIC.

Subjects who received CMM alone reported a 0.3-point increase from baseline.

12-MONTH RESULTS

Average VAS Pain Scores for 12-Month Time Point

Pain

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported an average decrease of 2.2 points from baseline VAS.

Subjects who crossed over to receive IDB in combination with CMM reported a 3-point decrease from baseline VAS.

Function

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported on average increase of 15 points in the SF-36.

Subjects who crossed over to receive IDB in combination with CMM reported an average increase of 17 points in the SF-36.

Disability

Subjects who received IDB in combination with CMM reported an average decrease of 14 points in ODI score.

Subjects who crossed over to receive IDB in combination with CMM reported an average decrease of 12 points in ODI score.

Click here for Instructions for Use

References:

- Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Agans RP, et al. The rising prevalence of chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(3):251–258.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With special features on socio-economic Status and Health. Hyattsville, MD. 2012.

- Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine 1995; 20(17):1878–83.

- DePalma MJ, Lee JE, Peterson L, et al. Are outer annular fissures stimulated during diskography the source of diskogenic low-back pain? An analysis of analgesic diskography data. Pain Med. 2009;10(3): 488–94.

- Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and

association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(2):116–27. - Levin DA, Hale JJ, Bendo JA. Adjacent segment degeneration following spinal fusion for degener-ative disc disease. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2007;65(1):29–36.

Advantages of Using COOLIEF* Cooled Radiofrequency

Advantages of Using COOLIEF* Cooled Radiofrequency